After His Arrest, Chance Marsteller Seeks Redemption

After His Arrest, Chance Marsteller Seeks Redemption

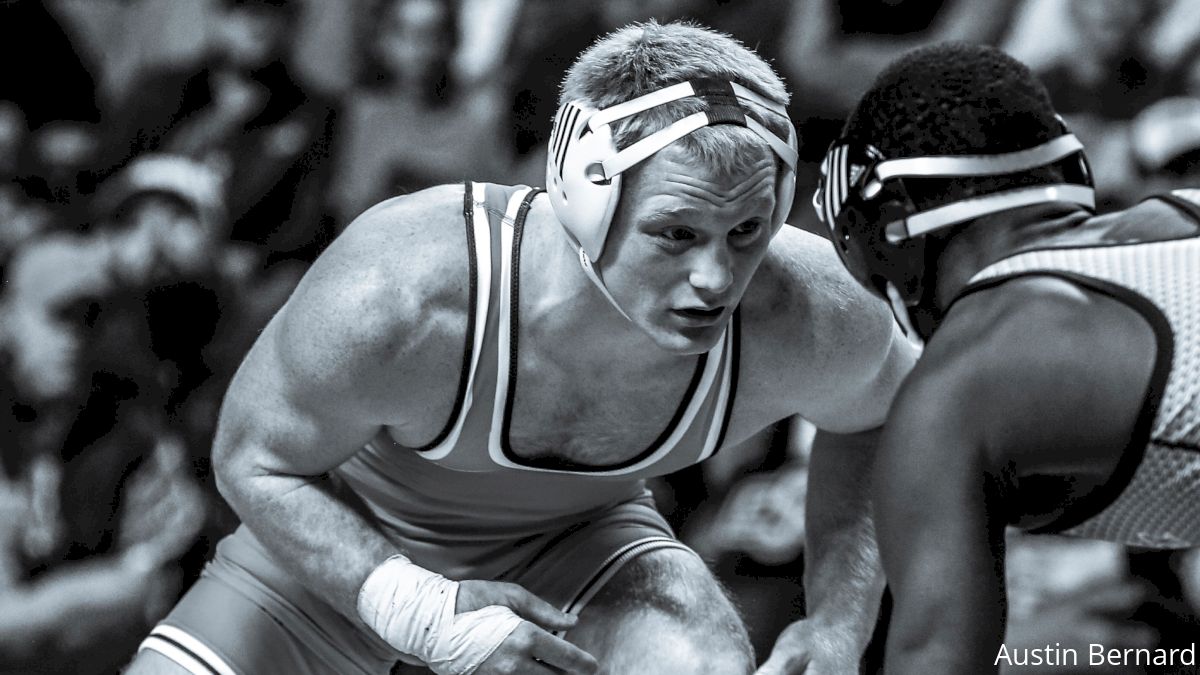

Chance Marsteller has had an up and down career and is now on the road to redemption and trying to simultaneously battle addiction and wrestling dreams.

By Storms Reback

On August 25, 2016, Chance Marsteller made a very big and very public mistake.

The wrestling community had a lot to say about the incident that saw the former high school prodigy from Pennsylvania get kicked out of Lock Haven University and thrust into the limelight for all the wrong reasons. Many of the comments made about him in online forums weren't very kind, but if you knew his entire story, how he was abandoned permanently by his biological father when he was five and for three years by his mother when he was in high school, you'd understand that his behavior that night wasn't just out of character, it was inevitable.

Chance's difficult upbringing helped create a mindset that has always set him apart from his peers. "He's bullheaded, stubborn, tenacious, and focused," said his mother Suzanne, "and he thinks about wrestling 24/7. He's got that fire in his belly."

For years, Chance was driven by that fire. It's what made him run five miles before dawn, do pushups until his arms gave out, and treat every match like it was a matter of life and death.

But here's the thing about fire: if you depend on it day in and day out, eventually you're going to get burned.

Chance Finds a Like-Minded Soul in Cary Kolat

After being introduced to wrestling by his older brother, John Stefanowicz, who's currently the No. 2-ranked Greco-Roman wrestler in the country, Marsteller discovered that he was pretty good at the sport -- but not good enough to beat George Weber, an early rival from Bel Air, Maryland. When Suzanne learned the secret to Weber's success, that he trained at Cary Kolat's club in Timonium, MD, she started taking Chance there several times a week.

Considered one of the greatest freestyle wrestlers the U.S. has ever known, Kolat possessed the sort of intensity that filled every cubic inch of his gym and inspired Marsteller to adopt a similar mentality. During a recent phone conversation, Marsteller provided a glimpse into Kolat's mindset. "If you want to become the best you can be, he's going to help you be the best you can be," said Marsteller, "but if you really don't want it, well, you can just go to the wayside. It's pretty much that simple."

The kid who made himself crank out 20 pullups every time he went to the basement of his house until he finally broke the chin-up bar had found a like-minded soul.

"He told stories about how he tried to better himself in every little way," Marsteller said. "Like at the gas pump, he'd hold the gas handle down instead of putting the click thing on so it would strengthen his fingers."

Marsteller also played football as a kid, but when he was 10, Kolat took him aside. "You can be pretty good at two sports when you grow up, or you can be really good at one," he said. "What do you want to do?"

"I want to be great at one," Marsteller said.

Kolat handed Marsteller a piece of paper and told him to list his goals.

Marsteller wrote down, "Olympic champion and world champion."

Chance Replicates Cary's High School Career

When Kolat landed a job at the University of North Carolina in 2010, Marsteller bounced around his home state of Pennsylvania, training with clubs such as Team Griffin in Harrisburg and the Dark Knights in East Stroudsburg. With his parents' assistance and old mats donated by his junior high, Marsteller also converted a barn on his family's 100-acre farm just outside of New Park, PA, into a wrestling training facility.

When he was 14, Marsteller started working out in the "wrestling barn" two or three times a day, six days a week, jumping rope, doing pushups and pullups, shadow wrestling, and conducting practices for those brave or crazy enough to join him.

"I ran practices for anyone who wanted to come and work out," he said.

As an eighth-grader, Marsteller started getting recruited by Division I schools and having his wrestling prowess compared to -- gulp -- LeBron James in basketball. He could have gone anywhere he wanted for high school, but when Suzanne asked Cary Kolat if they should be looking at other schools, he set her straight.

"Absolutely not," he told her. "Why change something that's not broke?"

The wrestling program at Kennard-Dale, the high school in nearby Fawn Grove, wasn't known for producing world-class wrestlers before Marsteller's arrival. He almost singlehandedly put the school on the map, attracting college recruiters and large crowds in the same way that Kolat once had at Jefferson-Morgan High School in Jefferson, PA.

With all the attention came pressure, but Marsteller welcomed it.

"I was like, 'Go ahead and bring it. I love it,'" he said. "The best athletes are supposed to want that. Honestly, the more hype there was, the more I enjoyed the sport. I wanted to wrestle every match like it was my last match or an Olympic final. You go out there and you have the same mindset against everybody, whether they're 0-20 or 100-0."

Marsteller managed to exceed expectations, going undefeated in high school and winning four Class AAA state championships, in what is arguably the most talented high school wrestling state in the country. Before him, only 11 high school wrestlers in Pennsylvania had won four state titles and only four others had gone undefeated. The last wrestler to do both? Cary Kolat, who went 137-0 from 1989 to 1992.

People naturally started comparing the two. They had the same build. They had the same drive. And they were both ambidextrous on the mat, capable of attacking with either hand.

But Marsteller never liked the comparison.

"I just wanted to be me," he said. "I always had my own goals. I wanted to make my own path. When I was a kid, I always told people I didn't want to be the second Cary. I wanted to be the first Chance."

Chance's Circuitous Route to Lock Haven

After being named USA Today's Wrestler of the Year in 2014, Marsteller was the No. 1-ranked recruit in the country coming out of high school. Overwhelmed by a recruiting process that saw him get hundreds of phone calls a day, he made a spur-of-the-moment decision to attend Penn State just three days into the process after its famed coach Cael Sanderson stopped by his house. After giving it a little more thought, Marsteller decided to visit Oklahoma State, where he fell in love with the program.

Backing out of his verbal commitment to Penn State and opting to go to Oklahoma State instead wasn't an easy choice for Marsteller, but he felt like it was a necessary one.

"When I made the Penn State decision, I felt really rushed and made a decision based on what I felt everybody else wanted me to do," he explained. "It weighed on me for a while. I felt like I needed to be my own person and make my own choice."

After redshirting his freshman year, Marsteller made his Oklahoma State debut on November 14, 2015, before 42,287 fans at Iowa's Kinnick Stadium. As exciting as his 14-11 win against Iowa's Edwin Cooper Jr. was, it may very well have been the highlight of what turned out to be a disappointing season in which he compiled a 6-5 record and saw his love of the sport nearly evaporate.

What had brought him to this low point? Marsteller places much of the blame on the decision to have him compete at 157 pounds, a weight he hadn't wrestled at since his freshman year of high school.

"I think most of it had to do with the weight cut," he said. "My senior in high school, I was at 180 almost the whole season. I dropped down to 170 for state. But 157 was just a whole other story."

The never-ending battle to lose weight also exacerbated Marsteller's growing homesickness.

"I was on my own a lot in high school, but I normally had somebody there for me like friends or family," he said. "At Oklahoma State, I was really disconnected. I got to the point where I'd be at practice and my body would be there but my mind wouldn't, and when you take your mind out of the sport, it's tough to stay on track."

As Marsteller grew increasingly distant from the team, he started gravitating toward the party scene on campus. When he finally got suspended from the team for an alcohol-related incident, it almost came as a relief. In Marsteller's eyes, the punishment -- he couldn't compete in matches but was still allowed to practice -- wasn't harsh enough.

"I didn't want to practice," he admitted. "I wanted to quit the team, just be done with the whole sport."

Four months later, in May 2016, he transferred to Lock Haven University. "I just wanted to get home. It was three hours from my house, but that's a lot closer than 22 hours from my house. I just wanted to be back in PA."

The Blow-Up

Although Marsteller doesn't admit to doing so consciously, by transferring to Lock Haven he was following in his mentor's footsteps. After spending his first two years of college at Penn State, Kolat transferred in 1995 to Lock Haven, where he won two national championships.

Marsteller could end up matching his mentor's achievements at Lock Haven, but to do so he's going to have to overcome a rocky beginning. On August 25, 2016, he was charged with aggravated assault, simple assault, recklessly endangering another person, disorderly conduct, and open lewdness after police arrested him for harassing the residents of an apartment complex in Lock Haven. He was subsequently kicked off the wrestling team and out of school and is currently serving a seven-year probation.

The fire that had fueled him for so long had exploded into an inferno he couldn't control.

The news of Marsteller's transgressions traveled far, wide, and fast and shocked those who only knew him by reputation. He'd always gotten excellent grades. He never showboated during a match or badmouthed an opponent afterward. And he was always unfailingly polite, addressing his elders as "ma'am" and "sir."

But those who know Marsteller the best will tell you that his meltdown had been brewing for years. We all have defining moments during our childhoods. Marsteller's came when he was five and his biological father told him, his mom, and his sister Shayna that he never wanted to see them again. The man made good on his promise but not before leaving his son with a vicious verbal jab: "Sorry, bud, but I love your mom, not you."

After his father took off, Chance's stepfather, Darren Marsteller, adopted him, something for which Chance has always been grateful.

"I have a great dad," he said. "He took me in when my [biological] dad left me, and I wouldn't consider him anything but my real dad."

Chance's home life took another difficult turn in high school when his parents separated and remained apart for nearly three years. After his mother moved to West Virginia, Chance stayed behind with Darren before living for varying chunks of time with an uncle, his girlfriend and her parents, and an assortment of friends.

Suzanne didn't sugarcoat the reason for her extended absence. "To be honest, I started drinking," she said. "I figured it was going to make things easier. Well, it didn't, and it was bad. That addiction, drinking, it's not a good thing."

Chance succeeded in turning his family's turmoil into motivation, training harder, longer, and more intensely than everyone else. But he also masked his anger and confusion with a steady diet of alcohol and, occasionally, drugs, and this unhealthy regime finally caught up to him at Lock Haven.

"He was self-medicating," said Suzanne, who has been sober and back together with Darren for the past four years. "He had a problem. He had so many different rejections in his life, and he never really liked himself. We would have these talks. I was like, 'You're so smart. You're this incredible talent. People gravitate to you. Why don't you like yourself?'"

Chance feels like he hit rock bottom at Oklahoma State and that he was actually getting better when he first arrived at Lock Haven.

"I still had issues," he said. "You don't just solve them on your own. But I was training my butt off, working harder than I had for a long time, and my love for the sport came back. But that stuff, drugs and alcohol, it just catches up with you. I'm actually glad that it did. It's probably the best thing that ever happened to me. I had to change."

The Goal Remains the Same

By all accounts, Marsteller is doing an excellent job of putting his life back together. He had a successful stint at rehab. He's gone to group and individual counseling. He got engaged to his longtime girlfriend, Jenna, in January. And he finished last semester with a 4.0 GPA after re-enrolling at Lock Haven.

Although he won't be able to rejoin the wrestling team until January, he's already been embraced as part of the family. He's surrounded by familiar faces -- most of his teammates are from Pennsylvania -- and he's currently being mentored by assistant coach Rob Weikel, who, having wrestled for Lock Haven and coached at Central Mountain High School, also has deep roots in the state.

"We talk every day," Weikel said. "The big thing we've been working on is that he has to have a small circle of friends, people he really trusts, because he's the type of kid who tries to please everybody. You can't be pulled in a hundred different directions. You need to live a simple life."

Weikel has given Marsteller similar advice to follow on the mat.

"I told him, 'Do what you do well and try not to do too much,'" Weikel said. "Before, he was trying to impress. 'No, you're out there wrestling for you. You're wrestling for your family. And that's it.' You can see a huge difference between where he was five months ago and now."

It helps that Marsteller has resumed wrestling at a weight that feels more natural to him. At the Bill Farrell Memorial International Open last November, he made it to the semifinals of the 74kg division before losing to his former Oklahoma State teammate Alex Dieringer.

After finishing seventh at the U.S. Open in April, Marsteller spent a week in North Carolina training with Kolat to prepare for the University Freestyle Nationals in June. Marsteller finished in first place in Akron and made it to the semifinals of the Senior Men's Freestyle World Team Trials the following weekend.

Marsteller downs Anthony Valencia At 2017 World Team Trials

As good as Marsteller has looked on the mat, he still has a long way to go before he fully recovers from the incident that occurred last August.

"Every day's going to be a battle for him, but I think he's on the right track," Weikel said. "He's a special person. He's going to be an excellent coach someday because he wants to help everyone."

Weikel isn't the only one who thinks that as good of a wrestler as Marsteller is, he's going to be an even better coach one day. Whenever Marsteller hasn't been able to wrestle, he's jumped at any opportunities to work with young wrestlers. When he dislocated his elbow in the eighth grade, he volunteered to coach his junior high teammates while he healed. When he got suspended from the Oklahoma State team, he helped prepare the Stillwater High School team for the state championships. And after the incident at Lock Haven, he worked as a volunteer assistant coach for the junior high team in Fawn Grove.

"I just like seeing people become the best they can be, seeing them raise their levels in the sport and in life," Marsteller said. "I have trouble sitting there watching kids not do something right."

Suzanne told a story about one of her son's opponents from a match earlier this year asking Chance about a move he'd used on him. A lot of wrestlers would have laughed, said something snarky, or simply walked away. Chance being Chance, he actually helped his opponent practice the move.

"Why would you teach him your secrets?" Suzanne asked Chance afterward.

"It's not a secret," he said. "It's just a wrestling move. I know I can counter it. It's better for him to know more."

Despite the unexpected hiccups Marsteller has experienced during his college wrestling career, he's confident he can still achieve the objectives he wrote down when he was 10 years old.

"My goals are 100 percent the same," he said. "But I've realized you can't look so far ahead all the time. A new goal of mine is to take it one day at a time, to never see anything as a setback, to learn as much as I can all the time, and to get better every day."

When asked about Marsteller's future, Weikel had a rosy outlook.

"We all know that wrestling is going to be a part of it," he said. "We just want to make sure he's a good person and he's able to help others along the way. I think if he gets that message the other stuff will take care of itself. As far as wrestling goes, the sky's the limit for him."

On August 25, 2016, Chance Marsteller made a very big and very public mistake.

The wrestling community had a lot to say about the incident that saw the former high school prodigy from Pennsylvania get kicked out of Lock Haven University and thrust into the limelight for all the wrong reasons. Many of the comments made about him in online forums weren't very kind, but if you knew his entire story, how he was abandoned permanently by his biological father when he was five and for three years by his mother when he was in high school, you'd understand that his behavior that night wasn't just out of character, it was inevitable.

Chance's difficult upbringing helped create a mindset that has always set him apart from his peers. "He's bullheaded, stubborn, tenacious, and focused," said his mother Suzanne, "and he thinks about wrestling 24/7. He's got that fire in his belly."

For years, Chance was driven by that fire. It's what made him run five miles before dawn, do pushups until his arms gave out, and treat every match like it was a matter of life and death.

But here's the thing about fire: if you depend on it day in and day out, eventually you're going to get burned.

Chance Finds a Like-Minded Soul in Cary Kolat

After being introduced to wrestling by his older brother, John Stefanowicz, who's currently the No. 2-ranked Greco-Roman wrestler in the country, Marsteller discovered that he was pretty good at the sport -- but not good enough to beat George Weber, an early rival from Bel Air, Maryland. When Suzanne learned the secret to Weber's success, that he trained at Cary Kolat's club in Timonium, MD, she started taking Chance there several times a week. Considered one of the greatest freestyle wrestlers the U.S. has ever known, Kolat possessed the sort of intensity that filled every cubic inch of his gym and inspired Marsteller to adopt a similar mentality. During a recent phone conversation, Marsteller provided a glimpse into Kolat's mindset. "If you want to become the best you can be, he's going to help you be the best you can be," said Marsteller, "but if you really don't want it, well, you can just go to the wayside. It's pretty much that simple."

The kid who made himself crank out 20 pullups every time he went to the basement of his house until he finally broke the chin-up bar had found a like-minded soul.

"He told stories about how he tried to better himself in every little way," Marsteller said. "Like at the gas pump, he'd hold the gas handle down instead of putting the click thing on so it would strengthen his fingers."

Marsteller also played football as a kid, but when he was 10, Kolat took him aside. "You can be pretty good at two sports when you grow up, or you can be really good at one," he said. "What do you want to do?"

"I want to be great at one," Marsteller said.

Kolat handed Marsteller a piece of paper and told him to list his goals.

Marsteller wrote down, "Olympic champion and world champion."

Chance Replicates Cary's High School Career

When Kolat landed a job at the University of North Carolina in 2010, Marsteller bounced around his home state of Pennsylvania, training with clubs such as Team Griffin in Harrisburg and the Dark Knights in East Stroudsburg. With his parents' assistance and old mats donated by his junior high, Marsteller also converted a barn on his family's 100-acre farm just outside of New Park, PA, into a wrestling training facility.When he was 14, Marsteller started working out in the "wrestling barn" two or three times a day, six days a week, jumping rope, doing pushups and pullups, shadow wrestling, and conducting practices for those brave or crazy enough to join him.

"I ran practices for anyone who wanted to come and work out," he said.

As an eighth-grader, Marsteller started getting recruited by Division I schools and having his wrestling prowess compared to -- gulp -- LeBron James in basketball. He could have gone anywhere he wanted for high school, but when Suzanne asked Cary Kolat if they should be looking at other schools, he set her straight.

"Absolutely not," he told her. "Why change something that's not broke?"

The wrestling program at Kennard-Dale, the high school in nearby Fawn Grove, wasn't known for producing world-class wrestlers before Marsteller's arrival. He almost singlehandedly put the school on the map, attracting college recruiters and large crowds in the same way that Kolat once had at Jefferson-Morgan High School in Jefferson, PA.

With all the attention came pressure, but Marsteller welcomed it.

"I was like, 'Go ahead and bring it. I love it,'" he said. "The best athletes are supposed to want that. Honestly, the more hype there was, the more I enjoyed the sport. I wanted to wrestle every match like it was my last match or an Olympic final. You go out there and you have the same mindset against everybody, whether they're 0-20 or 100-0."

Marsteller managed to exceed expectations, going undefeated in high school and winning four Class AAA state championships, in what is arguably the most talented high school wrestling state in the country. Before him, only 11 high school wrestlers in Pennsylvania had won four state titles and only four others had gone undefeated. The last wrestler to do both? Cary Kolat, who went 137-0 from 1989 to 1992.

People naturally started comparing the two. They had the same build. They had the same drive. And they were both ambidextrous on the mat, capable of attacking with either hand.

But Marsteller never liked the comparison.

"I just wanted to be me," he said. "I always had my own goals. I wanted to make my own path. When I was a kid, I always told people I didn't want to be the second Cary. I wanted to be the first Chance."

Chance's Circuitous Route to Lock Haven

After being named USA Today's Wrestler of the Year in 2014, Marsteller was the No. 1-ranked recruit in the country coming out of high school. Overwhelmed by a recruiting process that saw him get hundreds of phone calls a day, he made a spur-of-the-moment decision to attend Penn State just three days into the process after its famed coach Cael Sanderson stopped by his house. After giving it a little more thought, Marsteller decided to visit Oklahoma State, where he fell in love with the program.Backing out of his verbal commitment to Penn State and opting to go to Oklahoma State instead wasn't an easy choice for Marsteller, but he felt like it was a necessary one.

"When I made the Penn State decision, I felt really rushed and made a decision based on what I felt everybody else wanted me to do," he explained. "It weighed on me for a while. I felt like I needed to be my own person and make my own choice."

After redshirting his freshman year, Marsteller made his Oklahoma State debut on November 14, 2015, before 42,287 fans at Iowa's Kinnick Stadium. As exciting as his 14-11 win against Iowa's Edwin Cooper Jr. was, it may very well have been the highlight of what turned out to be a disappointing season in which he compiled a 6-5 record and saw his love of the sport nearly evaporate.

What had brought him to this low point? Marsteller places much of the blame on the decision to have him compete at 157 pounds, a weight he hadn't wrestled at since his freshman year of high school.

"I think most of it had to do with the weight cut," he said. "My senior in high school, I was at 180 almost the whole season. I dropped down to 170 for state. But 157 was just a whole other story."

The never-ending battle to lose weight also exacerbated Marsteller's growing homesickness.

"I was on my own a lot in high school, but I normally had somebody there for me like friends or family," he said. "At Oklahoma State, I was really disconnected. I got to the point where I'd be at practice and my body would be there but my mind wouldn't, and when you take your mind out of the sport, it's tough to stay on track."

As Marsteller grew increasingly distant from the team, he started gravitating toward the party scene on campus. When he finally got suspended from the team for an alcohol-related incident, it almost came as a relief. In Marsteller's eyes, the punishment -- he couldn't compete in matches but was still allowed to practice -- wasn't harsh enough.

"I didn't want to practice," he admitted. "I wanted to quit the team, just be done with the whole sport."

Four months later, in May 2016, he transferred to Lock Haven University. "I just wanted to get home. It was three hours from my house, but that's a lot closer than 22 hours from my house. I just wanted to be back in PA."

The Blow-Up

Although Marsteller doesn't admit to doing so consciously, by transferring to Lock Haven he was following in his mentor's footsteps. After spending his first two years of college at Penn State, Kolat transferred in 1995 to Lock Haven, where he won two national championships.Marsteller could end up matching his mentor's achievements at Lock Haven, but to do so he's going to have to overcome a rocky beginning. On August 25, 2016, he was charged with aggravated assault, simple assault, recklessly endangering another person, disorderly conduct, and open lewdness after police arrested him for harassing the residents of an apartment complex in Lock Haven. He was subsequently kicked off the wrestling team and out of school and is currently serving a seven-year probation.

The fire that had fueled him for so long had exploded into an inferno he couldn't control.

The news of Marsteller's transgressions traveled far, wide, and fast and shocked those who only knew him by reputation. He'd always gotten excellent grades. He never showboated during a match or badmouthed an opponent afterward. And he was always unfailingly polite, addressing his elders as "ma'am" and "sir."

But those who know Marsteller the best will tell you that his meltdown had been brewing for years. We all have defining moments during our childhoods. Marsteller's came when he was five and his biological father told him, his mom, and his sister Shayna that he never wanted to see them again. The man made good on his promise but not before leaving his son with a vicious verbal jab: "Sorry, bud, but I love your mom, not you."

After his father took off, Chance's stepfather, Darren Marsteller, adopted him, something for which Chance has always been grateful.

"I have a great dad," he said. "He took me in when my [biological] dad left me, and I wouldn't consider him anything but my real dad."

Chance's home life took another difficult turn in high school when his parents separated and remained apart for nearly three years. After his mother moved to West Virginia, Chance stayed behind with Darren before living for varying chunks of time with an uncle, his girlfriend and her parents, and an assortment of friends.

Suzanne didn't sugarcoat the reason for her extended absence. "To be honest, I started drinking," she said. "I figured it was going to make things easier. Well, it didn't, and it was bad. That addiction, drinking, it's not a good thing."

Chance succeeded in turning his family's turmoil into motivation, training harder, longer, and more intensely than everyone else. But he also masked his anger and confusion with a steady diet of alcohol and, occasionally, drugs, and this unhealthy regime finally caught up to him at Lock Haven.

"He was self-medicating," said Suzanne, who has been sober and back together with Darren for the past four years. "He had a problem. He had so many different rejections in his life, and he never really liked himself. We would have these talks. I was like, 'You're so smart. You're this incredible talent. People gravitate to you. Why don't you like yourself?'"

Chance feels like he hit rock bottom at Oklahoma State and that he was actually getting better when he first arrived at Lock Haven.

"I still had issues," he said. "You don't just solve them on your own. But I was training my butt off, working harder than I had for a long time, and my love for the sport came back. But that stuff, drugs and alcohol, it just catches up with you. I'm actually glad that it did. It's probably the best thing that ever happened to me. I had to change."

The Goal Remains the Same

By all accounts, Marsteller is doing an excellent job of putting his life back together. He had a successful stint at rehab. He's gone to group and individual counseling. He got engaged to his longtime girlfriend, Jenna, in January. And he finished last semester with a 4.0 GPA after re-enrolling at Lock Haven.Although he won't be able to rejoin the wrestling team until January, he's already been embraced as part of the family. He's surrounded by familiar faces -- most of his teammates are from Pennsylvania -- and he's currently being mentored by assistant coach Rob Weikel, who, having wrestled for Lock Haven and coached at Central Mountain High School, also has deep roots in the state.

"We talk every day," Weikel said. "The big thing we've been working on is that he has to have a small circle of friends, people he really trusts, because he's the type of kid who tries to please everybody. You can't be pulled in a hundred different directions. You need to live a simple life."

Weikel has given Marsteller similar advice to follow on the mat.

"I told him, 'Do what you do well and try not to do too much,'" Weikel said. "Before, he was trying to impress. 'No, you're out there wrestling for you. You're wrestling for your family. And that's it.' You can see a huge difference between where he was five months ago and now."

It helps that Marsteller has resumed wrestling at a weight that feels more natural to him. At the Bill Farrell Memorial International Open last November, he made it to the semifinals of the 74kg division before losing to his former Oklahoma State teammate Alex Dieringer.

After finishing seventh at the U.S. Open in April, Marsteller spent a week in North Carolina training with Kolat to prepare for the University Freestyle Nationals in June. Marsteller finished in first place in Akron and made it to the semifinals of the Senior Men's Freestyle World Team Trials the following weekend.

Marsteller downs Anthony Valencia At 2017 World Team Trials

As good as Marsteller has looked on the mat, he still has a long way to go before he fully recovers from the incident that occurred last August.

"Every day's going to be a battle for him, but I think he's on the right track," Weikel said. "He's a special person. He's going to be an excellent coach someday because he wants to help everyone."

Weikel isn't the only one who thinks that as good of a wrestler as Marsteller is, he's going to be an even better coach one day. Whenever Marsteller hasn't been able to wrestle, he's jumped at any opportunities to work with young wrestlers. When he dislocated his elbow in the eighth grade, he volunteered to coach his junior high teammates while he healed. When he got suspended from the Oklahoma State team, he helped prepare the Stillwater High School team for the state championships. And after the incident at Lock Haven, he worked as a volunteer assistant coach for the junior high team in Fawn Grove.

"I just like seeing people become the best they can be, seeing them raise their levels in the sport and in life," Marsteller said. "I have trouble sitting there watching kids not do something right."

Suzanne told a story about one of her son's opponents from a match earlier this year asking Chance about a move he'd used on him. A lot of wrestlers would have laughed, said something snarky, or simply walked away. Chance being Chance, he actually helped his opponent practice the move.

"Why would you teach him your secrets?" Suzanne asked Chance afterward.

"It's not a secret," he said. "It's just a wrestling move. I know I can counter it. It's better for him to know more."

Despite the unexpected hiccups Marsteller has experienced during his college wrestling career, he's confident he can still achieve the objectives he wrote down when he was 10 years old.

"My goals are 100 percent the same," he said. "But I've realized you can't look so far ahead all the time. A new goal of mine is to take it one day at a time, to never see anything as a setback, to learn as much as I can all the time, and to get better every day."

When asked about Marsteller's future, Weikel had a rosy outlook.

"We all know that wrestling is going to be a part of it," he said. "We just want to make sure he's a good person and he's able to help others along the way. I think if he gets that message the other stuff will take care of itself. As far as wrestling goes, the sky's the limit for him."